Parties can and do change. But these four barriers stand between the Republican Party and moderation.

By Pippa Norris

Feb. 8, 2021 at 7:45 a.m. EST Published in the Washington Post/Monkey Cage

Most congressional Republicans continue to embrace Trumpism, despite some wavering after the deadly Capitol riot. The GOP has backtracked on impeachment, with most Senate Republicans voting against holding an impeachment trial. State parties have punished Republicans such as Rep. Liz Cheney (Wyo.), who spoke and voted in favor of impeachment, rather than members such as Sens. Ted Cruz (Tex.) and Josh Hawley (Mo.), who supported the falsehood that the presidential election had been stolen. House Republicans did not sanction Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (Ga.), despite her past endorsements of wild conspiracy theories.

But the notion that the GOP would suddenly abandon Trumpism once Donald Trump left the White House has the basic story upside down. Trump wasn’t the cause of authoritarian populism; his success was the consequence of deeper underlying forces.

When do parties change?

Median voter theory suggests that there is a normal distribution of views in society, with most people clustered in the midpoint across the ideological spectrum. If so, the shock of major electoral defeats will push rational vote-seeking parties away from the extremes and back toward the political center, where they can harvest the most support. That’s particularly true in electoral systems requiring a majority of votes to win power, as parties realize that they need to broaden their appeal to gain support from moderates and independents. If they do not learn and adapt, if their only appeal is to the extremes, parties will remain in the electoral wilderness.

Under Trump, the GOP lost the House, the Senate and the White House. So unless Republicans don’t understand the true distribution of public opinion, which is always possible, any rational vote-seeking party should recognize the risks of the Trump brand and move the party back toward the conservative center-right.

Right?

Not so fast. Party rebuilding typically takes a long time, a lagged process typically occurring after the shock of a series of major electoral defeats. Four important barriers hinder GOP renewal.

Barrier 1: The Republican Party has adopted authoritarian-populist values

The first problem is that authoritarian-populist values have gone viral and spread deeply through the Republican Party. Expert estimates of political parties’ ideological positions suggest that the party of Lincoln has become willing to undermine democratic principles in pursuit of power, much like the Alternative for Germany, Austria’s Freedom Party and Hungary’s Fidesz. Other independent evidence confirms these estimates.

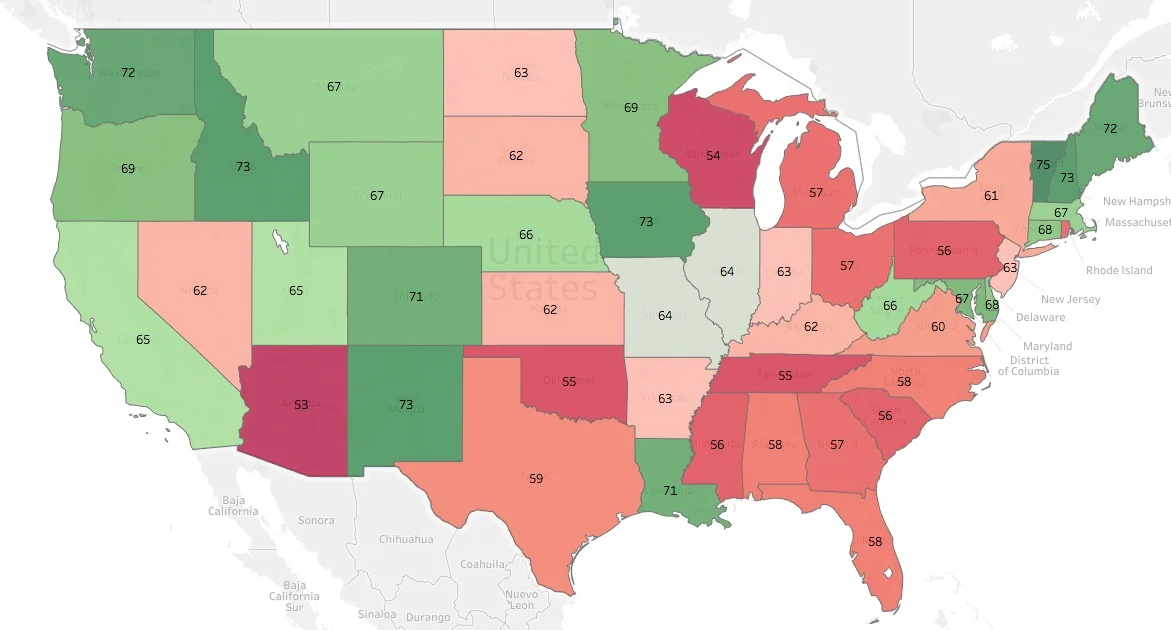

It’s not just Trump and the top congressional leaders who embrace authoritarian values. This mind-set has penetrated the party nationwide. In December, the Electoral Integrity Project asked 789 experts to estimate the ideological position of U.S. state parties. As you can see in the figure below, some state Republican parties, such as those in Vermont and Hawaii, continue to respect liberal democratic principles. But most, like those in Wisconsin and Nevada, have abandoned these values.

The MAGA base similarly doubts basic democratic principles, such as the integrity of American elections. Even since Joe Biden’s inauguration, about 8 in 10 Republican voters continue to endorse the “Big Lie” that the 2020 election was rigged and Biden’s victory is illegitimate.

Barrier 2: Republicans see diversity as a threat, not an opportunity

One reason so many Republicans are willing to believe that contests are rigged is that the party has gradually lost faith in its capacity to win the White House fair and square by respecting democratic principles, norms and practices. Since 1992, Republicans have not won a majority of the popular vote in seven out of eight presidential elections. Trump lost the popular vote by almost 3 million in 2016 and by 7 million in 2020.

Instead of adapting, Republicans have come to fear the growing ethnic and racial diversity of the American electorate as an existential threat to the party’s survival. When Republicans control the state legislature, instead of moving toward the center-right to expand support, they fiddle with the rules and rig the outcome in their favor. More than 100 new state legislative bills currently seek to restrict voting rights, particularly affecting communities of color.

Barrier 3: Institutional incentives

Moreover, the institutional incentives facing individual Republican lawmakers diverge from the collective interest of the party in seeking to win the White House. The structural rules of the game insulate congressional Republicans from needing to broaden their appeal.

The House (since 2010), the Senate and the electoral college have all been asymmetrical disproportional, meaning that Republicans have a built-in advantage in translating their share of the popular vote into seats. As a result, Republican members of Congress can get elected in White and rural America. But the party has repeatedly been unable to win a majority of the popular vote for the White House with this strategy.

Gerrymandering means that Republicans can also win House seats by appealing to their MAGA base in safe districts. Where parties are deeply polarized, this tendency is reinforced by primaries and caucuses, which typically engage the most partisan voters. Lawmakers fear angering primary voters, even if this means ignoring their district’s general electorate.

Barrier 4: Party cultures are slow to change

Finally, the party’s unwillingness to abandon Trumpism is reinforced by institutional inertia. Congressional Republicans got elected under Trump, so why should they change? It’s risky. Normally, any party must be shocked by successive landslide electoral defeats to oust the old regime. Party renewal grows from subsequent electoral gains, gradually bringing moderate new blood into the party. So far, the reverse has been happening as moderates leave in despair and QAnon acolytes step up. Enough are elected to Congress to block liberal legislation and trigger gridlock.

Parties can and do learn. They can move closer to the median voter. But congressional Republicans haven’t suffered the shock of landslide defeats. Rather, the party has gained House seats, insulated by gerrymandering.

Republicans could abandon authoritarian populism and move back toward the traditional conservative center-right — becoming the party of Mitt Romney (Utah), Susan Collins (Maine) and Lisa Murkowski (Alaska). A minority seeks to do so. But fearing the dedicated MAGA base’s wrath, and hoping that new restrictions on voting rights will help win seats in the 2022 midterm elections, the Trumpist wing in Congress has an incentive to block party renewal.

Pippa Norris

Pippa Norris, the McGuire lecturer in comparative politics at Harvard University, is the founding director of the Electoral Integrity Project and a co-author, with Ronald Inglehart, of “Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism.”Follow