A free and fair election requires a context where – among other things – political parties and candidates can register and campaign freely, information is available for public deliberation, and votes are fairly translated into seats. These factors enable citizens to choose (and change) their government freely. However, these principles are under threat in many countries by populist authoritarian regimes that gain and maintain control through the manipulation of the media and autocratic legalism. The latter phenomenon is exemplified by the democratic façade created by leaders such as Viktor Orbán in Hungary, in an attempt to legitimize their regime. These leaders undermine democracy legally, make changes underneath the surface, and remove or control key democratic institutions and procedures. This undermines citizens' ability to make informed choices, rendering the election process a mere façade for the biases and manipulations behind the scenes. While election day itself might be mostly free of irregularities, especially since 2012, it is in the pre-voting phase where biases and manipulation are rooted.

The façade of the electoral system: gaining legitimacy with biased rules

Using elections to gain legitimacy is an old tactic: autocratic leaders from the Soviet Union to Cuba have used elections to create a democratic façade. In 2010, for the first time since the democratization of Hungary, power was concentrated in the hands of a single political power. Following the parliamentary elections in 2010, with a supermajority, the Fidesz-KDNP Party Alliance introduced a new electoral law written behind closed doors and without plural political debate. Without any transparency, the government created a new map of constituencies with districts that varied drastically in size and heavily benefitted Orbán’s party coalition Fidesz-KDNP. In addition, the law replaced two-round elections in single-member constituencies with a majority support with a Winner-Take-All system; legalized “voter-tourism”; “winner compensation”; and strategically granted citizenship and voting rights to 450,000 near-abroad citizens who were known to support Fidesz. These innovations helped him secure a two-thirds majority in both 2014 and 2018. Viktor Orbán and his party alliance are also constantly changing the law to make it more difficult for the opposition to unite and campaign.

This unfair nature of the electoral system contributed to the outstanding success of Fidesz in previous elections, along with the manipulation of media. Orbán transformed the majority of the traditional media outlets into pro-government propaganda, reducing market plurality and political independence of the media.

Assessing the façade

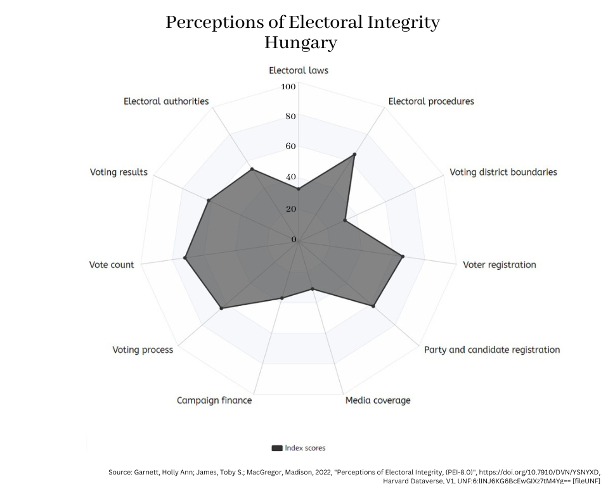

The OSCE’s ODIHR Election Observation Mission concluded that although election day in 2022 only experienced minor irregularities, the election, in general, was “marred by the absence of a level playing field”. This is supported by the Electoral Integrity Project’s evaluation of the quality of elections in Hungary. As Figure 1 shows, while election day activities (voting process, vote count and vote results) score relatively well, the rest of the components – related to the broader environment in which elections take place – score significantly lower. Low scores on electoral laws, boundary delimitation, campaign media and campaign finance reveal the true nature of Orbán’s electoral authoritarianism. We see in these data a system which seemingly looks democratic but does not offer real opportunities for competition.

Figure 1. Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, Hungary

Call for a closer look

In 2022, the European Parliament deemed Hungary undemocratic, assigning the label of electoral autocracy to its regime. In response, the country’s Foreign Minister, Péter Szijjártó, used the narrative of the elections to legitimize their regime and criticised the European Parliament due to their lack of respect towards Hungary's electorate. However, while in Hungary there are no military personnel encouraging you to vote, and ballots are not marked beforehand, elections still take place in a

system designed by the ruling party alliance and where the opposition cannot campaign with equal conditions and is denied the same opportunities for winning seats. Just because votes are not stolen systematically on election day does not mean that citizens are not robbed of having real options. As the data shows, the Hungarian electorate is deprived of this right. This raises doubts about the possibility of the democratic removal of Orbán's regime, even if the opposition unites. Thus, a thorough examination is required to understand how to challenge such regimes in the future.

Sandor Adam Gorni is a final year master's student in political science at Uppsala University. His academic interests include democratic backsliding, right-wing populism, political participation, voting behaviour, and post-soviet political culture.